Board of Governors and Board of Trustees Work With Staff and Volunteers to Fulfill the ABR’s Mission

By Brent Wagner, MD, MBA, ABR Executive Director

2024;17(5):3

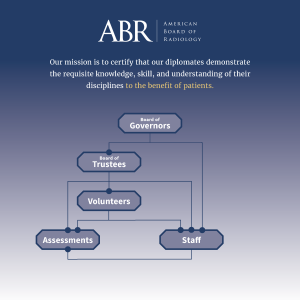

The ABR has two governing bodies staffed by volunteers: the Board of Governors (BOG) and the Board of Trustees (BOT). The following chart illustrates the connections among these two groups, our approximately 1,300 volunteers, and about 100 full-time staff. For more information, please see this article.

Click on the image for an interactive pdf.

New Residents Excited to Start Their Training Days

By Rodney Campbell, ABR Communications Manager

2024;17(5):10

This past summer, future diagnostic and interventional radiologists completed their internships and started residencies. We caught up with six of them to see what they think of the experience so far and what they expect from their training.

Amanda Bronte Balon, MD

Mount Sinai Medical Center

“Starting residency was both exciting and overwhelming. Radiology builds on the clinical skills we’ve developed over the past five years but also requires us to master the entirely new skill of interpreting and reporting on images. Within the first week of residency, I realized how extensive and broad the specialty of radiology is and the effort needed to bridge that knowledge gap. Although this thought can be intimidating, I’ve felt incredibly supported by my program, attendings, and co-residents as I take these initial steps. I have experienced the rewards of contributing to patient care and recognized how central radiologists are to many healthcare decisions.”

Christina Caviasco, MD

Vanderbilt University Medical Center

“I’m grateful to be training at Vanderbilt University Medical Center with such patient and passionate mentors. They have reminded me that they were once in my position as a fledgling radiologist with what seems like an endless amount of information to learn. Our more senior residents have been helpful in offering advice and laid out a path to success in terms of tackling the first few months. I am eager to continue to learn and feel so supported by my program.”

Maclean M. Cook, MD

University of Virginia Medical Center

“Starting my radiology residency has been an exciting and demanding journey. I’m thrilled to finally immerse myself in the specialty I’ve been passionate about since medical school. At the same time, I’m navigating a new medical lexicon and trying to absorb the vast knowledge necessary for radiology. Fortunately, the unwavering support from my residency program has been invaluable. The enthusiasm and dedication of my attendings during our readouts have already made a significant impact on my growth. I’m encouraged by the progress I’ve made and am eager for the learning that lies ahead.”

Mary Mahoney, MD

Fox Chase Cancer Center

“This past July, I enthusiastically embarked on the four-year odyssey that is a radiation oncology residency. I am grateful to be undertaking this journey at Fox Chase Cancer Center, where I feel supported by my co-residents, attendings, and staff. Although learning the mountain of knowledge and clinical skills required is daunting, I remind myself that it takes four years to become a radiation oncologist for a reason. Every day I am convinced I learn at least 20 new things! I cannot believe how much I have learned, and I cannot wait to see how much I grow by the end of the four years.”

Kushi Mallikarjun, MD

Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology

“I will never forget my first day in the reading room as a radiology resident. I had been looking forward to starting formal radiology training for several years, and the moment had finally come! I always knew the learning curve would be overwhelming (it certainly has been), but I did not expect such close support from my attendings and senior residents. The most exciting part of the first few months of radiology residency was going home every day feeling that I was palpably more knowledgeable and more capable than I was the previous day. We are learning every second of the day in our specialty and I hope it never stops.”

Jesse Smith, MD

Oregon Health and Science University Hospital

“I am finally in my radiology training! On my first day on service, I grabbed the Dictaphone, opened a study, and realized I had no idea what to say. Since then, I have encountered nothing but support from my seniors and attendings. Radiology is so fulfilling yet so challenging. It almost feels like I am starting medical school all over again. Each day brings so many new learning experiences that it is hard to fathom how much I will learn in four years. After such a long wait, it feels great to finally be in my chosen field!”

New DR Oral Exam Builds on Previous Model with Scoring Rubrics

By Stephen F. Simoneaux, MD, and Desiree E. Morgan, MD, ABR Governors; Mary S. Newell, MD, ABR Associate Executive Director for Diagnostic Radiology; and Brent Wagner, MD, MBA, ABR Executive Director

2024;17(5):6

For the Diagnostic Radiology Certifying Exam, the ABR will be transitioning from a computer-based exam to an oral exam in 2028. The development of the new model benefited from iterative contributions of a wide range of external stakeholders, and the subsequent decision to return to an oral exam format was largely focused on a specific goal: to create an exam that assesses the higher order skills that are part of clinical practice (in contrast to knowledge assessable on a multiple-choice exam).1

For the Diagnostic Radiology Certifying Exam, the ABR will be transitioning from a computer-based exam to an oral exam in 2028. The development of the new model benefited from iterative contributions of a wide range of external stakeholders, and the subsequent decision to return to an oral exam format was largely focused on a specific goal: to create an exam that assesses the higher order skills that are part of clinical practice (in contrast to knowledge assessable on a multiple-choice exam).1

In communications related to the change, the ABR compared the 2028 model with the legacy ABR oral exam that existed for decades through 2012. In conveying that the 2028 version will be different from the old DR oral exam, we have unintentionally created the impression for some faculty and candidates that we have not retained some of the attributes and principles of the legacy exam.

The previous and upcoming models both represent composite assessments based on cases presented by and discussed with several examiners during a series of 25-minute one-on-one sessions covering the different subspecialty content areas of radiology. Candidates analyze cases based on their observations of the imaging features and available history and summarize their findings in the form of a reasonable differential diagnosis before suggesting next steps (e.g., additional imaging, urgent referral for consideration of surgery, etc.). The analysis by the candidate resembles a succinct summary that might be part of a multidisciplinary conference, a concise but complete report, or a phone conversation with the treating physician. The examiner might ask clarifying questions or redirect the candidate to the major findings or alternative diagnostic possibilities. Each candidate is assessed by the specific group (panel) of examiners who discussed the cases with them. In the panel discussions, scores for individual sections may be raised if low performance in a particular subject area is considered an outlier.

The most obvious difference in the new exam is that it will be administered remotely using a one-on-one videoconference format. Less apparent to the candidate will be our efforts to mitigate subjectivity and bias in the exam. For example, cases will be given in the same order for each session, and each category will have an identical case set for a given oral exam date. As a result, all candidates examined on a Tuesday will see very similar content (although the number of cases might vary, depending on how quickly the examiner and the candidate can complete a case and move to the next).

Examiners in the old model used a general scoring grid that included three broad categories: observation (identifying the abnormality and pertinent negatives), synthesis (differential diagnosis, including the most likely diagnosis), and management (for example, additional imaging or urgent referral). The new model will build on these by defining specific elements (a rubric) to be used by all examiners as part of the electronic score sheet for each case.

For example, a conventional set of abdominal radiographs in a young adult with vomiting might demonstrate distended loops of gas-filled small bowel. A pertinent negative would be the absence of free air. A second finding would be a subtle lucency overlying the right inguinal region. Additional testing would be a CT scan with intravenous contrast. The major CT finding would be a right inguinal hernia containing thickened ileum with diminished enhancement. The overall management (urgent surgical consultation) would be based on a presumptive diagnosis of ischemic bowel within an incarcerated inguinal hernia. More detailed examples of performance rubrics are being prepared for the seven content areas by the ABR’s subject matter experts in diagnostic radiology and are scheduled to be posted on the ABR’s website by November 25.

The major goal of the new exam model is to assess the knowledge and skill of diagnostic radiologists. To that end, residents should prepare for the exam in a way that allows them to identify and appropriately communicate the presence and nature of imaging findings, the potential significance of those findings, and reasonable recommendations for next steps. The use of defined rubrics for each case will enhance standardization of objective scoring of the discussions.

- Larson DB, Flemming DJ, Barr RM, Canon CL, Morgan DE. Redesign of the American Board of Radiology Diagnostic Radiology Certifying Examination. Am J Roentgenology 2023;221(5). https://www.ajronline.org/doi/10.2214/AJR.23.29585