The History of Medical Physics Certification

by G. Donald Frey, PhD, Associate Executive Director, Medical Physics

2020;13(2):4

Medical physics is a profession that combines a deep knowledge of physics, a good working knowledge of relevant medicine, and the ability to partner with physicians. Our path to certification was a bit different from our physician colleagues, but it was driven by the same forces, including:

- Commitment to quality.

- Ensuring that practitioners are properly educated.

- Ensuring that a certified physicist is qualified to practice.

The First Step – Licensure

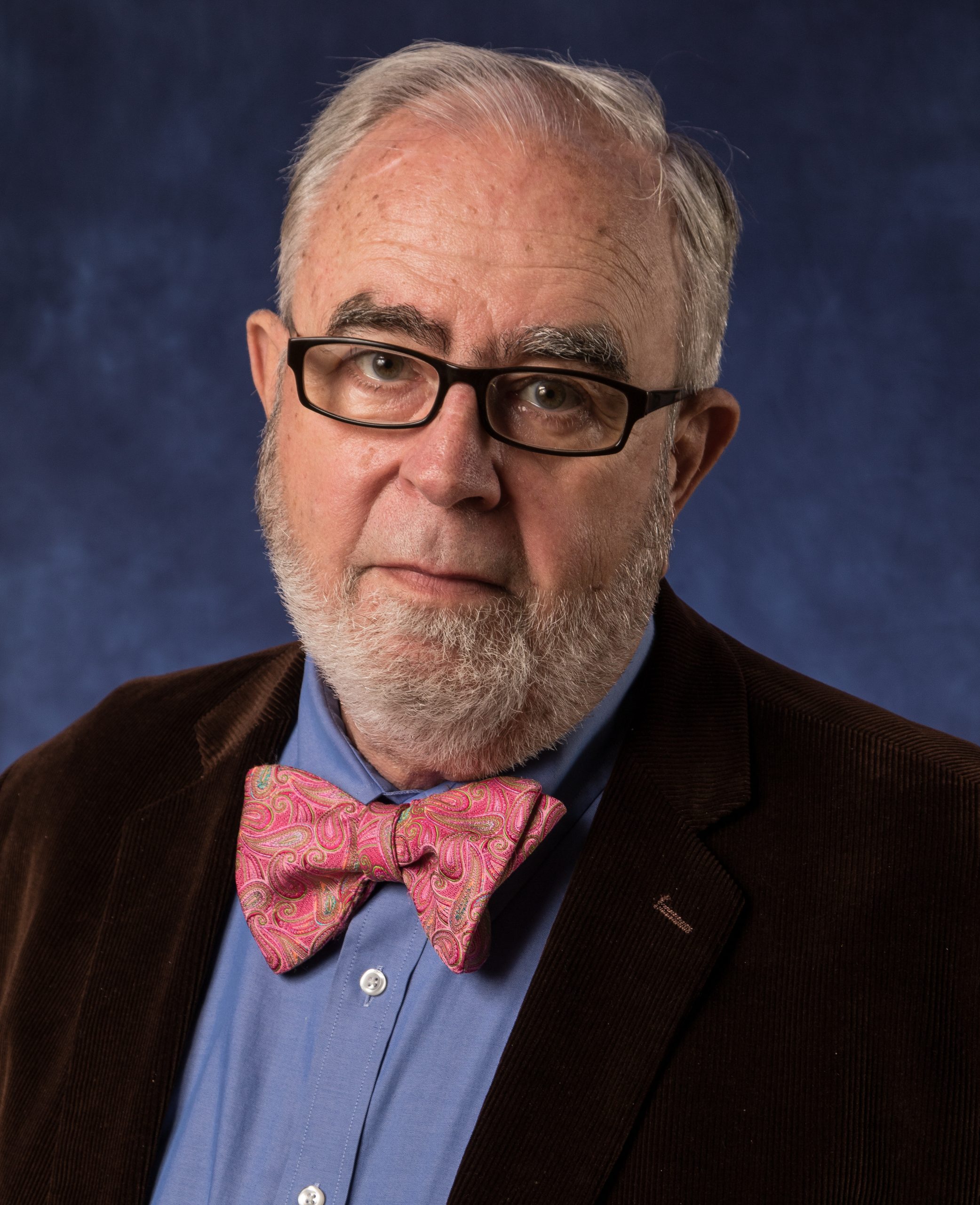

Medical physics did not exist until after the discovery of x-rays by Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen (figure 1) in 1895. From the start, however, we were on the path to certification because of efforts already underway in the wider world of medicine. In the years following the Civil War, there were many concerns about quality in medicine. In the absence of licensing, many unqualified individuals declared themselves to be physicians. Properly trained physicians’ concerns about quality led them to form the American Medical Association (AMA) in 1847 to improve medical practice. Their mission statement, much like the ABR’s, is “To promote the art and science of medicine and the betterment of public health.”

One of the main goals of the AMA was to have the states develop a licensing requirement that kept nonqualified physicians from practicing.1 Because the effort was done state by state, it took a long time, but by 1915 most states had good licensing schemes. The crucial component was that in most jurisdictions, both a diploma in medicine and an examination were required. In this era of substandard medical schools, some jurisdictions could judge the quality of the medical school and reject those deemed to be deficient. Early on, registration schemes were tried and found to be ineffective. The process of licensing was strengthened by the development of groups dedicated to assuring quality and uniformity. These groups merged in 1912 to become the Federation of State Medical Boards. This organization still exists and is a significant factor in physician licensing.2

The Second Step – Improving Medical Education

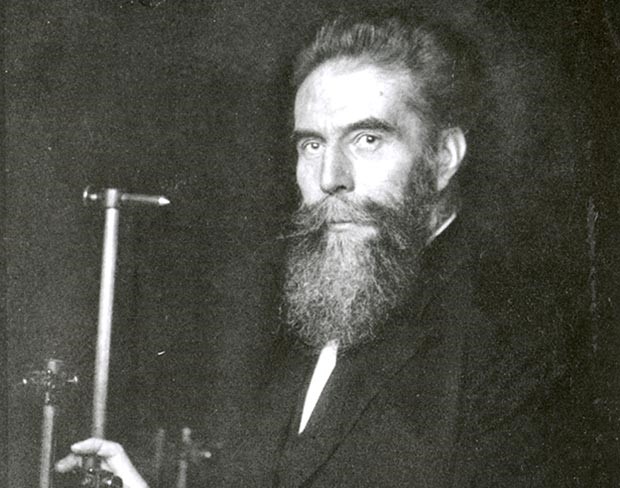

The improvements in medical education that occurred more than 100 years ago had a profound influence on the modern practice of medical physics. In this period, many medical schools in the United States were proprietary and were effectively diploma mills. In all cases, from the best to the worst, there was no national standard as to how physicians should be trained. The amount of clinical training and how it was obtained also varied widely. The group driving the reform of medical education is often called “The Hopkins School,” because several of the group were on the faculty of Johns Hopkins University.3 The key figure, however, was Abraham Flexner (figure 2), a man who had devoted his life to improving education but who had never even been in a medical school before starting research for his famous report.

Flexner’s work on education in general had caught the attention of Henry Pritchett, head of the Carnegie Foundation. Pritchett immediately recognized the qualities Flexner could bring to a report on medical schools, and Flexner undertook this task with great energy and commitment. He visited every medical school in the United States and Canada. The report that he issued was a scathing indictment of medical education (figure 3).4,5

Flexner assigned medical schools to one of three categories based on his evaluation:

- A first group consisted of those that compared favorably with Hopkins.

- A second tier comprised schools considered substandard but able to be remediated.

- A third group was rated of such poor quality that closure was indicated.

One-third of all American medical schools closed after his report was issued.6,7 Flexner’s report was a great impetus for the improvement in medical education. Admission standards, a standardized curriculum, state chartering, and clinical training all became the norm. These advances helped create a pool of much better trained physicians.

The Third Step – The Board Certification Movement

As more physicians started specializing, a movement began to ensure quality in the different specialties through the creation of medical boards. From the start, there was a commitment to keeping the board movement autonomous and focused on quality rather than on excluding competition. The key points were:

- The boards would be independent from the professional societies.

- The boards were not controlled by the AMA.

- The boards would be independent from the states.

- The skills necessary to practice in the specialty were the focus.

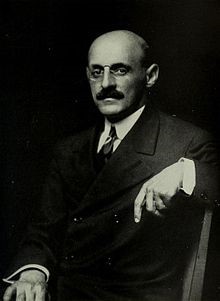

The American Board of Ophthalmology (figure 4) was the first board established and was soon followed by others. Realizing they needed an umbrella organization to coordinate efforts and maintain quality, four medical boards came together in 1934 to found the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS): Dermatology; Obstetrics and Gynecology; Ophthalmology; and Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery. The ABR was created that same year and joined the ABMS in 1935. At that time, radiologists were usually generalists and practiced diagnostic radiology and radiation oncology. As those areas diverged after World War II, it became customary to become certified in one or the other.8 Certification in interventional radiology/diagnostic radiology (IR/DR) was added just last year.

Medical Physics Certification

The struggles of physicians to be licensed was very similar to the quest to have licensure for medical physicists. In the 1920s, radiologists realized the need for properly trained medical physicists. In that era, there were no medical physics schools and physicists usually had their training in larger therapy facilities. Accurate and safe radiation treatments, both teletherapy and brachytherapy, required a well-trained medical physicist. In 1934, the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) initiated a certification program for medical physicists. This program was well accepted, but around 1940, the forward-thinking leaders of radiology realized that the certification program should be an ABR function. Until then, ABMS Member Boards certified only physicians. The transfer was delayed until after WW II, but in 1947, the ABR began certifying medical physicists.

Some of the distinguished medical physicists in the inaugural certification class included Marvin Williams, James Weatherwax, Otto Glasser, Henrietta Hayden, Carl Braestrup, and Edith Quimby. Rosalyn Yalow, the only ABR diplomate (in any discipline) to win the Nobel Prize, was in the second class. At that time, there were two specialties for medical physicists: traditional radiology, which was largely radiation therapy, and medical nuclear physics, which became important after many medically useful radionuclides became available. Then, as the imaging modalities available in diagnostic radiology expanded (ultrasound, CT, and MRI), the need for diagnostic physicists grew. Thus, today there are three primary certificates in medical physics: therapeutic medical physics, nuclear medical physics, and diagnostic medical physics.

Most states register rather than license medical physicists. (Medical physicists are only licensed in Florida, Hawaii, New York, and Texas.) This is generally ineffective because the states often deem poorly qualified individuals as medical physicists. This makes ABR certification even more important.

With a standard training program, medical physics residencies, a strong professional organization, and, most of all, ABR certification, medical physics has developed into a strong vibrant profession with the same commitment to quality that our physician predecessors envisioned more than a century ago.

Footnotes

-

- Hamowy R. The early development of medical licensing laws in the United States, 1875-1900. J Libert Stud 1979;3(1):73-119. This article is written from a libertarian perspective but gives a detailed history.

- Johnson D, Chaudhry HJ. The history of the Federation of State Medical Boards: Part One — 19th century origins of FSMB and modern medical regulation. J Med Regulation 2012;98(1):20-29.

- Duffy TP. The Flexner Report ― 100 Years Later. Yale J Bio Med 2011;84(3):269-276.

- Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada. Washington, DC: Science & Health Publications Inc; 1910.

- When I read the Flexner report, I can’t help but think of medical physics education in the era before the formation of CAMPEP. –GDF

- Flexner shared the prejudices of his age and recommended that only two of the traditional black medical schools remain open.

- The one women’s medical school in the U.S., the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania, survived.

- Even though the ABR did not certify medical physicists at that time, medical physicists were on the oral examining panels. Edith Quimby is an example.